Menu

ESI Stories

How Do You Bridge Divides in Climate Change Conversations? A Q+A with Ben Stillerman, Deb Roy, and Laur Hesse Fisher

By: Sophia Apteker, Administrative and Communications Assistant

During Earth Month, the internet has been abuzz with a spectrum of conversations about the current and future state of our planet. And while the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication has categorized the majority of Americans as Alarmed or Concerned about global warming, roughly a third are still Disengaged, Doubtful, and Dismissive. This begs the question: How do we catalyze the latter audience to recognize what the climate fuss is all about and mobilize them for action?

On Tuesday, April 30, the MIT Environmental Solutions Initiative will be partnering with the MIT Department of Earth, Atmospheric & Planetary Sciences (EAPS) to present a film screening of True False, Hot Cold. The documentary was shot in a county of Utah with the least belief in climate change in America. It weaves vignettes from farmers, ranchers, cowboys, coal miners, and other county residents together to build bridges — not divides — between people who have very different identities and beliefs.

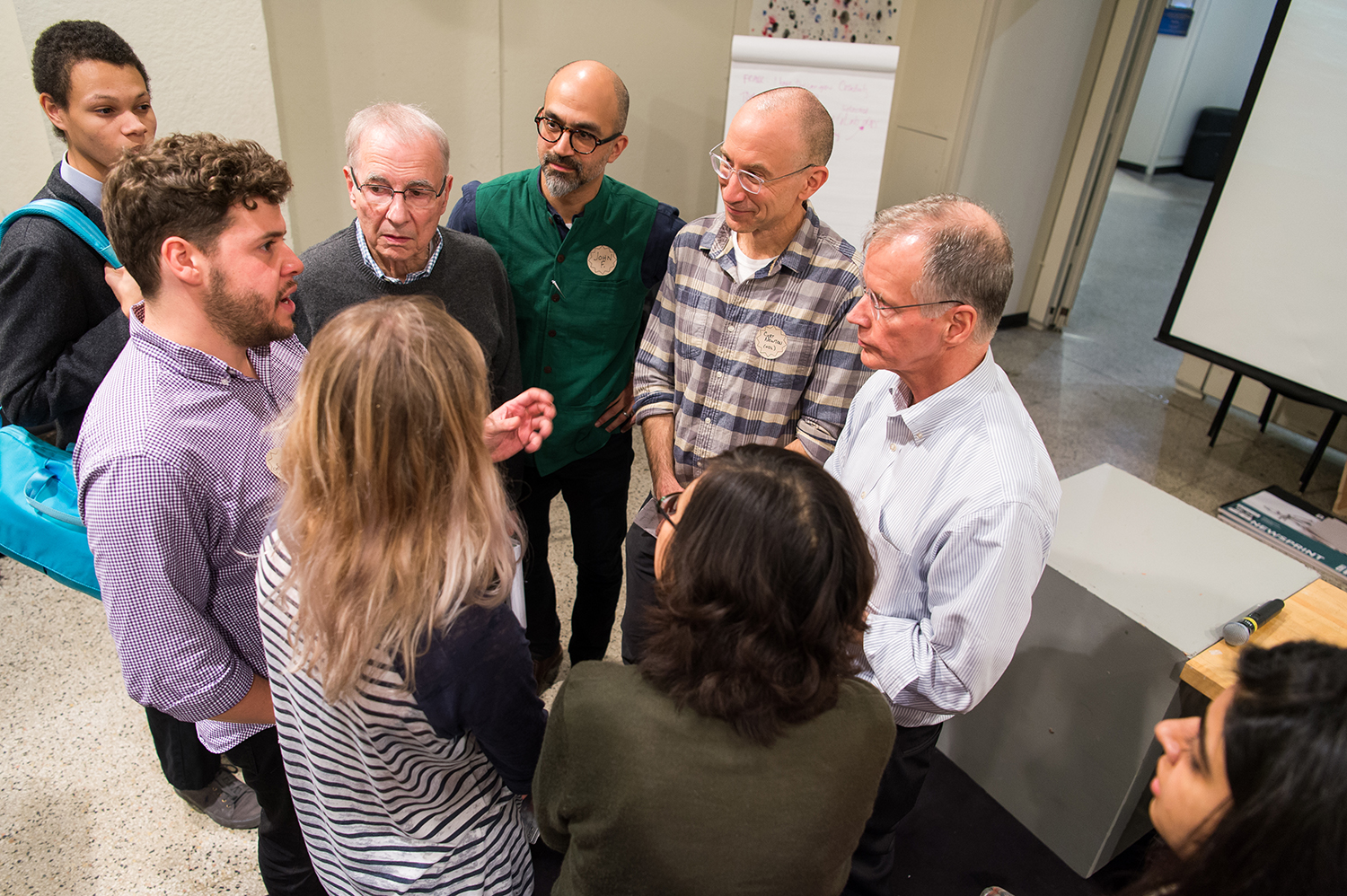

The screening will be accompanied by a discussion with Ben Stillerman, filmmaker and founder of the Social Cohesion Lab; Deb Roy, faculty director of the MIT Center for Constructive Communication; and Laur Hesse Fisher, program director at MIT Climate and founder of the MIT Environmental Solutions Journalism Fellowship. These panelists, who are actively incorporating these bridge-building values and approaches into their work, will also have an open conversation with the audience.

This event is sponsored by the MIT Climate Nucleus.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

1. Ben and Laur: each of your projects — Ben with the film, Laur with the journalism fellowship — attempt to connect with hard-to-reach communities on climate change. Why is this topic important to you?

BS: Well here’s a simple way of thinking about that question, and it’s something I ask people who feel uncomfortable about giving airtime to people with wildly different opinions about a topic as big as climate change: How’s it working out for us right now, when we’re not able to talk to communities who disagree with us or are different from us? Doesn’t seem to be working that well, does it? The feeling of polarized animosity has stalled progress, so although a rural community might have different ideas about how to deal with climate, I think that the social value of connecting with them is greater than the risk of not hearing from them entirely.

LHF: Climate change has become a politically polarized issue in the United States. Yet a country free of carbon pollution requires the support of Americans across political parties and across the country – in the voting booth and also, critically, in the city halls and neighborhoods where the energy transition is happening. Still, opportunity exists, as an increasing number of Republicans, especially young Republicans, say that they are worried about climate change and many support the same climate solutions as Democrats. Building bipartisan support for climate solutions is within our grasp, but we need to approach it thoughtfully and humbly.

2. It seems like people might be hesitant to share their opinions if they don’t know how their words are going to be used. With this in mind, Ben, how did you convince people to let you interview them for the documentary?

BS: This might seem counterintuitive, but on big, controversial topics, I’ve found that people are eager to have their voices heard, especially when given the opportunity to share their beliefs in the context of their life experience. Everyone likes to feel that their story is worth hearing. In practice for our film, I showed up one afternoon at the Main Street gas station, introduced myself, and asked if people knew anyone worth talking to about some of these topics. Once I had done one interview and proved I wasn’t out to belittle or trick people, they were happy to suggest someone else worth chatting with, and because I now had the added validation from the first person, the door was already half open.

3. Deb, your expertise lies within using human-machine systems to develop deep systematic listening, which has applications in large scale social media ecosystems. What could we learn by using these listening techniques in the climate space?

DR: Our approach brings together facilitated dialogue, sensemaking, and digital technology to surface patterns of experience – rooted in personal stories – rather than opinions. This form of listening fosters a deeper understanding of what people value and how those values intersect with climate issues.

For example, through The Museum for the UN’s Global We initiative, we collected hundreds of conversations in 25 locations around the world and shared underheard local perspectives on climate directly with leaders at the UN COP28 summit. One of the questions that was asked was: “Imagine that the quietest voices on climate change were heard – what are they saying?” We also engaged 25 young people around the world to make sense of these conversations, building a transparent youth-owned process that activated and empowered local community members around climate.

4. Deb and Laur, we need to engage millions of people on climate change, yet in a way that’s personal to them. How can we effectively build connections at scale?

DR: We need to create opportunities for people to engage in meaningful personal actions. Meaningful because they are clearly connected to something bigger. Personal because they are actions that an individual has the power and agency to perform. In our work we seek to create scalable systems for dialogue and listening that create opportunities for people in communities from all walks of life to organize, design, facilitate, and analyze conversations they host with people in their trusted networks. Our main focus is to help communities build the capacity they need to surface and make sense of the voices of their peers using tools that are designed to empower them to analyze and interpret their own data.

LHF: Local news is the outlet that Americans rely on and trust the most, and studies show that localizing climate change is an effective way to open perspectives on the issue. Yet climate journalism is often limited to national and specialty news outlets. In order to engage Americans where climate change is disputed or underreported, we need to make it local — told by local messengers and centering local issues and values. This is the mission underlying the MIT Environmental Solutions journalism fellowship and a way we see we can help scale conversations about climate change in the parts of the country where it greatly matters.

5. What kinds of media do you consume and how does that shape your work?

BS: Is there a word for being addicted to Reddit? That’s what I am. I really love the weird feeling of always being one click away from devoted communities of people posting dozens of articles a day about things I sometimes totally disagree with, alongside reviews of lawn mowers or traffic reports from India. Although Reddit is often wrong, angry, or opinionated, it’s almost always passionate and fun, so it’s where I get a lot of the ideas which interest me for further investigation.

DR: I try to read news sources across a range of political perspectives, together with some news aggregators and public commentators that I trust.

LHF: This is a little cheesy but the media that is most effective for me are one-on-one conversations about climate change with people who don’t see what all the fuss is about. I learn what they’re hearing about climate change and solutions, what their concerns and frustrations are, and, when I can, where they get their information. It’s an incredible source of learning.

6. Who do each of you look to for inspiration?

BS: Two of my all-time heroes are Studs Terkel and Frederick Wiseman. Terkel, in his oral histories, was able to use deeply human narratives to ground his examination of massive topics like war or work. Wiseman, in his documentaries, is brave enough to let the people and institutions he profiles speak for themselves, without letting his own editorializing overshadow them.

DR: I am lucky to have an incredible network of mentors, advisors, colleagues, students, and family members who are constant sources of inspiration and who push me to aim higher while keeping grounded in real and practical progress.

LHF: Our journalism fellow alums are smart, thoughtful and committed to the audiences they serve. Their passion for tackling these issues with care and excellence is a great source of inspiration. I greatly admire the work and perspectives of Prof. Arlie Russell Hochschild, author of Strangers in their Own Land, and Prof. Katharine Hayhoe, a celebrated climate scientist and communicator. What brings me the most inspiration are the millions of people all around the world who are working boldly on reducing global emissions in their part of the world.

7. What kinds of projects can people expect to see from the Social Cohesion Lab (from which the True False, Hot Cold film emerged), the MIT Center for Constructive Communication, and this year’s journalism fellowship?

BS: We’re focused on two things: First, we’re planning on telling more stories about people and places with different ideas about right and wrong, true and false, in an effort to bridge divides through documentary. Second, we’re running “Depolarization Day” events using our documentaries, alongside guest speakers and a taught curriculum, as an engaging way to teach the skills of bridging to college students and interested communities.

DR: We have ambitious plans to advance and scale tools and methods for dialogue, listening, and deliberative decision-making. A first opportunity for some of this work will be right here at MIT where we are planning the launch of a dialogue and listening program for our undergraduate students this fall.

LHF: We’re accepting fellowship applications until April and the fellow stories will start dropping this summer! I’ll be reposting all the stories here, and you can also follow our media or sign up for our newsletter for updates. You can learn about the incredible impact of previous fellows.

8. What is one tip you have for people who want to respectfully engage in a discourse with someone that holds a different belief than them?

BS: Everyone holds their own belief with as much internal logic as you hold yours; no one is walking around thinking their beliefs are built on shabby reasoning. Remembering this really helps keep an open heart when someone holds a position that you think is totally wrong. And stay humble, because of the thousands of beliefs you hold big and small, the chance that you’re right about them all is almost certainly zilch.

DR: Start by asking them to share their personal experiences about the topic or issue rather than their opinions, be willing to do the same for them, and commit to truly listening.

LHF: I love Ben and Deb’s replies! I’ll add, be curious, find shared values, and set appropriate expectations. Regarding that last one, I wouldn’t expect that you will be able to change someone’s mind. But if you come out of the conversation understanding their values and perspectives — and they understand and respect yours — that is a big win.

Register for the ‘True False, Hot Cold’: Film Screening & Discussion here.